In the modern industrial and educational landscape, we have become complacent about the black rectangles in our pockets. We view tablets, laptops, scanners, and power tools as benign tools of the trade—essential, boring, and safe. We toss them into bins, stack them on desks, and plug them into wall outlets without a second thought.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!But if you strip away the sleek plastic casing and look at the chemistry inside, the reality is far more volatile. A Lithium-Ion battery is essentially a controlled chemical reaction waiting to happen. It is energy density packed into a pressurized shell.

When you have one device, the risk is statistically negligible. But when you aggregate fifty or a hundred of them in a confined space—a server room, a classroom closet, or a warehouse depot—you are no longer just storing electronics. You are managing a hazardous material storage site.

The danger isn’t that the devices don’t work; it’s that they work too well. And when they fail, they fail with a ferocity that most facility managers are completely unprepared for. The phenomenon is called “Thermal Runaway,” and it is the hidden arsonist in your tech closet.

The Chemistry of the Spark

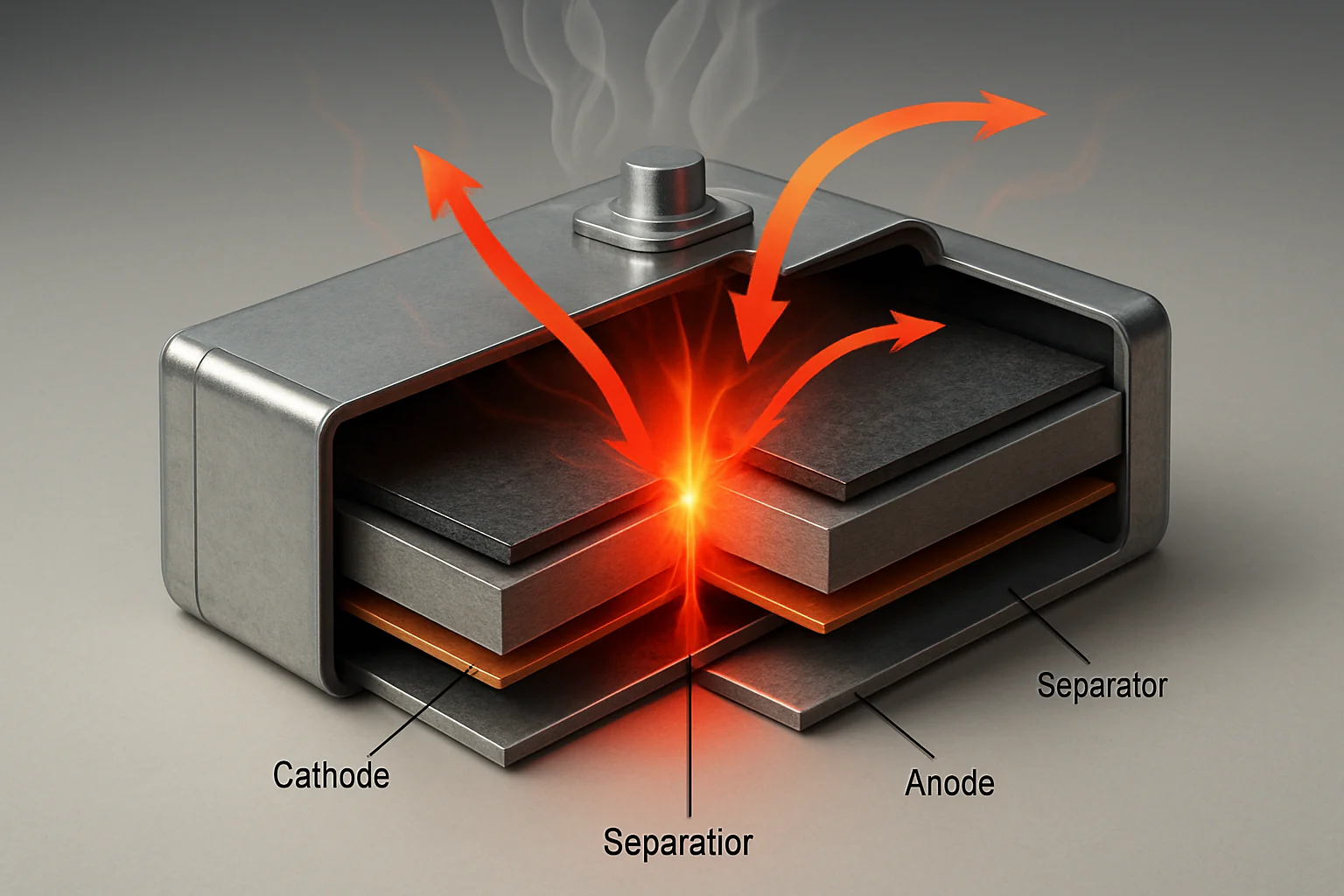

To understand the fire risk, we have to look inside the cell. A Lithium-Ion battery consists of a cathode, an anode, and a liquid electrolyte, separated by a microscopic piece of porous plastic called a separator.

When a battery charges, ions move from the cathode to the anode. This process generates heat. Under normal conditions, the device dissipates this heat into the air.

However, if the battery is damaged (dropped on a warehouse floor), overcharged (left plugged in with a faulty regulator), or exposed to external heat, the separator can fail. When the anode and cathode touch, a short circuit occurs inside the cell.

This internal short circuit causes the temperature to spike instantly to over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The liquid electrolyte boils and vaporizes, creating immense internal pressure. Eventually, the casing ruptures, venting toxic, flammable gas. If there is a spark—or simply enough heat—that gas ignites.

This is not a “fire” in the traditional sense of wood burning. It is a chemical fire. It does not need oxygen from the air to burn initially; it is self-sustaining. And it is incredibly difficult to extinguish.

The “Cluster” Multiplier

The real nightmare for a facility manager is not a single device catching fire; it is the “Cluster Effect.”

In many makeshift charging setups—wooden shelves, plastic bins, or open carts—devices are stacked directly on top of or next to each other. If Tablet A enters thermal runaway, it acts as a blowtorch directed at Tablet B.

Tablet B might be perfectly healthy, but the external heat from Tablet A melts its separator. Tablet B enters thermal runaway and ignites Tablet C.

Within minutes, a single faulty battery can trigger a chain reaction that consumes the entire fleet. The combined energy density of 30 laptops is roughly equivalent to a small stick of dynamite. If this happens in a closet full of cardboard boxes or cleaning supplies, the resulting structural fire can level a building.

The “Ventilation Void”

The primary catalyst for this disaster is often the enclosure itself.

Consumer electronics are designed to be air-cooled. They rely on ambient airflow to keep the battery temperature within a safe range during the charging cycle.

When organizations try to save money by building DIY charging stations (e.g., retrofitting a wooden cupboard or using a standard metal locker), they often neglect airflow. They drill a hole for the cords but forget about the heat.

When you plug in 40 devices in a sealed wooden cabinet, the ambient temperature inside the cabinet rises. As the ambient temperature rises, the batteries charge less efficiently and generate more heat. It is a feedback loop. If the internal temperature of the cabinet exceeds 110°F or 120°F, you are pushing those batteries into the “danger zone” where chemical instability becomes likely.

The Physics of Containment

So, how do you prevent the warehouse from burning down? You cannot change the chemistry of the batteries, but you can change the physics of their environment.

This is where the distinction between “storage” and “charging infrastructure” becomes life-saving.

- Passive vs. Active Ventilation: A proper containment system uses thermodynamics to move air. It features louvered vents positioned at the bottom (intake) and top (exhaust) to create a natural convection current. Heat rises, pulling cool air in from the bottom. In high-density setups, active fans are required to force-evacuate the hot air, keeping the ambient temperature neutral.

- Fire-Resistant Materials: Wood is fuel. Plastic melts. Industrial steel is a barrier. If a battery ignites inside a heavy-gauge steel enclosure, the fire is contained. The steel won’t burn. It prevents the flames from spreading to the drywall or the carpet. It buys the fire suppression system time to work.

- Smart Power Cycling: The most advanced defense is to stop the heat at the source. “Smart” charging systems don’t charge every device at once. They cycle power to different banks of outlets—charging devices 1-10 for 15 minutes, then devices 11-20. This reduces the total electrical load and the total heat output, keeping the cabinet temperature manageable.

The Human Factor: The “Drop”

Finally, we must address the human element. In industrial environments, devices get dropped. A scanner falls off a forklift. A tablet slides off a workbench.

This impact can create microscopic cracks in the battery separator. The device still works, but it is now a ticking time bomb.

If you allow employees to pile these devices haphazardly on a shelf, that damaged unit is pressed against others. Organized, slotted storage prevents physical contact between devices. It ensures that if one “bad apple” fails, it is physically separated from the rest of the barrel.

Conclusion

We often treat our technology fleets as assets to be managed by the IT department, focusing on software updates and screen repairs. But from a risk management perspective, a fleet of charging batteries is a facility issue. It is a fire safety issue.

The transition from “plugging it in wherever” to a dedicated, engineered solution is not just about organizing cords; it is about respecting the volatility of the energy source. By utilizing robust Global Industrial charging cabinets that are engineered with flow-through ventilation and steel containment, you are placing a firewall between the inevitable chemistry of the battery and the structural integrity of your building. You are acknowledging that while you cannot prevent every spark, you can certainly prevent the inferno.